Power from fusion has proved too hard to generate at scale. Can recent breakthroughs and massive investment change that?

By Arthur Turrell

hysicist Vaughn Draggoo inspects the target chamber during its construction at the National Ignition Facility in Livermore, California, October 2001. Photograph: Joe McNally/Getty Images

On 8 August 2021, a laser-initiated experiment at the United States National Ignition Facility (NIF), based at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, made a significant breakthrough in reproducing the power source of the stars, smashing its own 2018 record for energy released from nuclear fusion reactions 23 times over. This advance saw 70% of the laser energy put in released as nuclear energy. A pulse of light, focused to tiny spots within a 10-metre diameter vacuum chamber, triggered the collapse of a capsule of fuel from roughly the size of the pupil in your eye to the diameter of a human hair. This implosion created the extreme conditions of temperature and pressure needed for atoms of hydrogen to combine into new atoms and release, kilogram for kilogram, 10m times the energy that would result from burning coal.

The result is tantalisingly close to a demonstration of “net energy gain”, the long sought-after goal of fusion scientists in which an amount greater than 100% of the energy put into a fusion experiment comes out as nuclear energy. The aim of these experiments is – for now – to show proof of principle only: that energy can be generated. The team behind the success are very close to achieving this: they have managed a more than 1,000-fold improvement in energy release between 2011 and today. Prof Jeremy Chittenden, co-director of the Centre for Inertial Fusion Studies at Imperial College London, said last month that “The pace of improvement in energy output has been rapid, suggesting we may soon reach more energy milestones, such as exceeding the energy input from the lasers used to kickstart the process.”

If you’re not familiar with nuclear fusion, it’s different from its cousin, nuclear fission, which powers today’s nuclear plants by taking big, unstable atoms and splitting them. Fusion takes small atoms and combines them to forge larger atoms. It is the universe’s ubiquitous power source: it’s what causes the sun and stars to shine, and it’s the reaction that created most of the atoms we are made of.

Scientists have long been excited about fusion because it doesn’t produce carbon dioxide or long-lived radioactive waste, since the fuel it requires – two types of hydrogen known as deuterium and tritium – is plentiful enough to last for at least thousands of years, and because there is zero chance of meltdown. Unlike renewables such as wind and solar power, plants based on fusion would also take up little space compared with the power they would be able to generate.

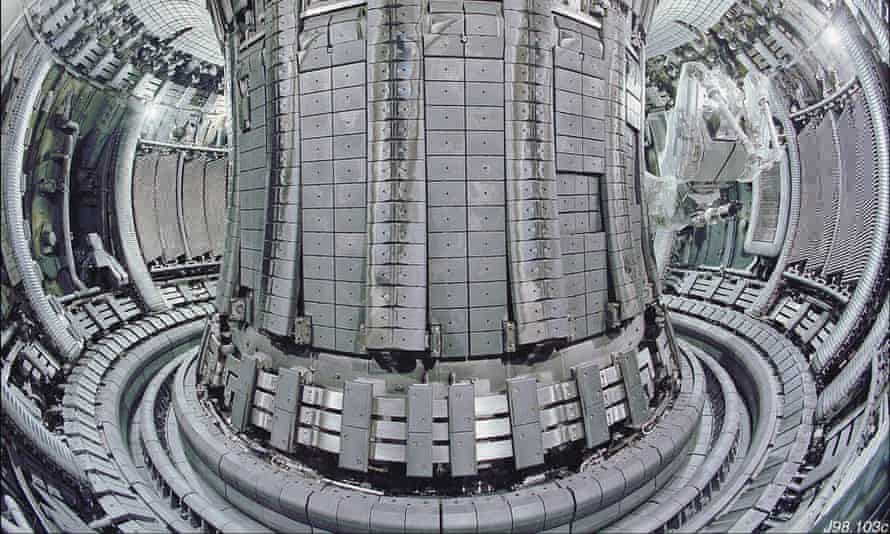

The Tokamak of the Joint European Torus (Jet) at the Culham Science Centre – which will soon to attempt to produce the largest amount of fusion energy so far. Photograph: AFP/Getty Images

However, because the NIF’s breakthrough is about demonstrating the principle only, the total amount of energy generated is not very impressive; it’s only just enough to boil a kettle. Nor does the gain measurement account for the energy used to run the facility, just what’s in the laser pulse. Despite this, it is nevertheless a landmark moment in the decades-long quest to produce fusion energy and use it to power the planet – which is, perhaps, the greatest scientific and technological challenge humanity has ever undertaken.

Although the experiment may have happened in a vacuum, NIF’s advance has not, and the pace of progress in fusion may surprise some long-time sceptics. Even Dr Mark Herrmann, head of the NIF’s fusion programme, says the latest development was “a surprise to everyone”. Many recent advances have been made with a different type of fusion device, the tokamak: a doughnut-shaped machine that uses a tube of magnetic fields to confine its fuel for as long as possible. China’s Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak (East) set another world record in May by keeping fuel stable for 100 seconds at a temperature of 120m degrees celsius – eight times hotter than the sun’s core. The world’s largest ever magnetic fusion machine, Iter, is under construction in the south of France and many experts think it will have the scale needed to reach net energy gain. The UK-based Joint European Torus (Jet), which holds the current magnetic fusion record for power of 67%, is about to attempt to produce the largest total amount of energy of any fusion machine in history. Alternative designs are also being explored: the UK government has announced plans for an advanced tokamak with an innovative spherical geometry, and “stellarators”, a type of fusion device that had been consigned to the history books, are enjoying a revival having been enabled by new technologies such as superconducting magnets.

For now, publicly funded labs are producing results a long way ahead of the private firms – but this could change

This is a lot of progress, but it’s not even the biggest change: that would be the emergence of private sector fusion firms. The recently formed Fusion Industry Association estimates that more than $2bn of investment has flooded into fusion startups. The construction of experimental reactors by these firms is proceeding at a phenomenal rate: Commonwealth Fusion Systems, which has its origins in MIT research, has begun building a demonstration reactor in Massachusetts; TAE Technologies has just raised $280m to build its next device; and Canadian-based General Fusion has opted to house its new $400m plant in the UK. This will be constructed in Oxfordshire, an emerging hotspot for the industry that is home to private ventures First Light Fusion and Tokamak Energy as well as the publicly funded Jet and Mast (Mega Amp Spherical Tokamak) Upgrade devices run by the UK Atomic Energy Authority.

Some of the investors in these firms have deep pockets: Jeff Bezos, Peter Thiel, Lockheed Martin, Goldman Sachs, Legal & General, and Chevron have all financed enterprises pursuing this new nuclear power source. For now, publicly funded labs are producing results a long way ahead of the private firms – but this could change.

With such progress, interest, and investment – and net energy gain perhaps just one or two more improvements away – perhaps it’s time to retire the old joke, so cliched it has been banned by editors at the Economist, that “fusion is 30 years away… and always will be”.

Junior UK science minister Amanda Solloway and Nick Hawker, CEO of First LIght Fusion, inspecting the company’s £1.1m “Big Gun” device, which the Oxfordshire firm hopes will help them achieve fusion and deliver clean energy. Photograph: Matt Alexander/PA

But it does depend on what we mean by “fusion” in that context; the scientists and their backers are now focusing on the bigger objective of fusion as a viable power source like fission, solar or wind. This requires far more than just “breakeven” in energy: a functioning fusion power plant would probably need at least 30 times the energy out for energy put in. However, scaling up the gain in energy is but one difficulty in making fusion a viable power source. A commercial reactor will have to solve several tricky engineering problems such as extracting the heat energy and finding materials that will withstand the relentless bombardment the reactor chamber will receive over its lifetime. Fusion reactors must also be self-sufficient in tritium, one of the two types of hydrogen that are fed in as fuel. For this, it is necessary to surround the reactor chamber with lithium because its atoms are converted to tritium when struck by the most energetic products of fusion – and this process has yet to be demonstrated at scale.

Those pursuing fusion have long known of the obstacles, but – with limited resources – achieving the immediate goal of gain has been a bigger priority. That’s beginning to change as fusion scientists and engineers look beyond scientific proof of principle. Around the world, several recently opened facilities are dedicated to solving these problems and, although they’re not trivial, everyone in fusion is confident that the obstacles can be overcome: progress depends on investment and will.

To find examples of how these two factors can be transformative, look no further than the pandemic. A sudden shot of both investment and motivation transformed the use of mRNA to fight disease from a wild idea to an accepted technology in the form of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines. Katalin Karikó, whose foundational work on mRNA has been key to the success of the technology, had the will to persevere for many years with little recognition and even less funding. Her dedication, and that of her colleagues, combined with a massive investment in development, testing and deployment is what enabled the vaccines to be ready in record time. The world wanted this, and we made it happen.

Global heating has made the need to turn carbon-free fusion energy into a usable power source ever more urgent. The world’s response thus far has been lackadaisical: it’s 2021 and more than 80% of global primary energy consumption still comes from coal, oil and gas. Fossil fuel consumption actually increased between 2009 and 2019 (though it fell in 2020 as most of the world locked down to help prevent the spread of Covid-19). While progress to date has been slow, most nations have pledged to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. Dr Ajay Gambhir, a senior policy research fellow at the Grantham Institute for Climate Change, Imperial College London, says most electricity generation needs to come from near-zero carbon sources as soon as 2030 in order to achieve this. Dr Michael Bluck, also of the Grantham Institute, expresses serious doubts that commercial fusion energy will be ready in time, saying that it is “very difficult to see this [conventional tokamaks] happening until after 2050” and that laser fusion has “another 50 years to go, if at all”.

Construction of the magnetic Tokamak of the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (Iter) in south-eastern France. The project is a collaboration between 35 countries. Photograph: Clement Mahoudeau/AFP/Getty Images

Those working in fusion do recognise that time is of the essence, and it’s part of what is motivating the recent acceleration. The startups’ vision necessarily sees fusion power being deployed at an unprecedented rate. “If we want to contribute to net zero by 2050 we need to be building plants, multiple, in the 2040s,” Nick Hawker, CEO of First Light Fusion, tells me. And who says the fusion firms couldn’t do it with the right tailwind? We would never have believed that a vaccine, let alone the first mRNA vaccine, could be developed and approved within a year instead of over decades.

The scale of the climate challenge is so immense that we need to throw the kitchen sink at it. That means renewables, fission, energy storage, carbon capture, and any other lifeline humanity can grab. If the world doesn’t have the will to at least try to deploy fusion energy too, it would be a missed opportunity. Fusion could afford people in developing countries the same energy consumption opportunities as people in developed nations enjoy today – rather than the global cutbacks that may be necessary otherwise. And we are likely to need fusion well beyond 2050, too: as a source of large-scale power to extract the carbon dioxide we’ve already put into the atmosphere, and because it’s the only feasible way we can explore space beyond Earth’s immediate vicinity.

Whether commercial fusion energy is ready in time to help with global warming or not depends on us as a society and how badly we want – no, need – star power on our side.